Firstly, I would like to acknowledge the traditional owners of this land, past and present, the Gadigal people of the Eora nation.

Ten years ago, Clover Moore, the lord mayor of Sydney, talked at the National Maritime Museum. She said: today, as we mark the beginning of Refugee Week, it is important to remember that all non‐Indigenous Australians are immigrants to this land.’

She continued, ‘From the perspective of thousands of years of Aboriginal custodianship, the rest of us are newcomers’. I wonder what the Gadigal people in 1788 thought as they watched sailing ships coming up their harbour? Did they realise that their civilisation was about to be uprooted? Did they watch with interest and wonder? How soon did that interest turn to mortal fear?

It has been a 200-year journey for their descendants to reassert the right to be free of those fears, to acclaim pride in their traditions. That’s a long wait.

The theme of this year’s Australia Day address is that freedom from fear is very special to all of us. To appreciate the value of freedom one must first be denied it. To know real fear gives special meaning and yearning to being free of fear.

So what does ‘freedom from fear’ entail for you and me as Australians, or those who ‘want to be Australians’ in 2016?

Let me share with you parts of my story. It may be unfamiliar to those who have been born and grown up in a peaceful Australia. To those who have come as refugees from the world’s trouble spots, parts of this story will be too familiar. A point of this story is to emphasise how very lucky we are to enjoy freedom from fear, and how very unlucky are many, many others who neither choose, nor deserve their fate.

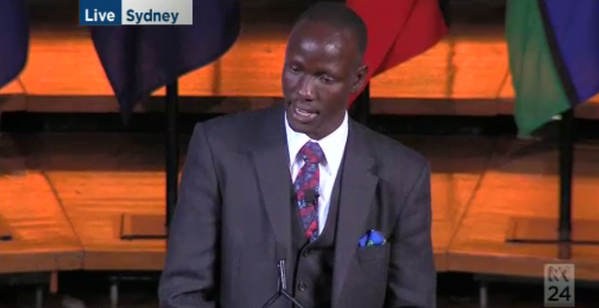

I was born in a small fishing village called Malek, in the South Sudan. My father was a fisherman and we had a banana farm. I am one of eight children born to Mr Thiak Adut Garang and Ms Athieu Akau Deng. So the parts of my name are drawn from both my parents. My given name is Deng which means god of the rain. In those parts of this wide brown land that are short of water my name might be a good omen. I have a nickname: Auoloch, which means swallow. Alas I couldn’t fly and as a young boy, about the age of a typical second grader in Sydney, I was conscripted into an army.

As they took me away from my home and family I didn’t even understand what freedoms I had lost. I didn’t understand how fearful I should have been. I was young. I was ignorant. I lost the freedom to read and write. I lost the freedom to sing children’s songs. I lost the right to be innocent. I lost the right to be a child.

Instead, I was taught to sing war songs. In place of the love of life I was taught to love the death of others. I had one freedom – the freedom to die and I’ll return to that a little later.

I lost the right to say what I thought. In place of ‘free speech’, I was an oppressor to those who wanted to express opinions that were different to those who armed me, fed me, told me what to think, where to go and what to do.

And there was something else very special to me that was taken away. I was denied the right to become an initiated member of my tribe. The mark of ‘inclusiveness’ was denied to me.

I had to wait until I became an Australian citizen to know that I belonged.

As an Australian I am proud that we have a national anthem. It’s ours and to hear it played and sung is to feel pride, pride that we are a nation of free people. It has a historical background that is familiar to those who grew up here, but which is not easily understood by newcomers. I found it useful to take some lines from our anthem to bring together what I want to share with you.

To be here today, talking about freedom from fear, about the rewards that come from thinking ‘inclusively’, rather than thinking ‘divisively’, is to achieve something that the child conscript Deng could not imagine.

I came to Australia as an illiterate, penniless teenager, traumatised physically and emotionally by war. In Sudan, I was considered legally disabled, only by virtue of being black or having a dark skin complexion. As you can see I am very black and proud of my dark skin complexion. But in the Sudan my colour meant that my prospects could go no further than a dream of being allowed to finish a primary education. To be a lawyer was unthinkable. Australia opened the doors of its schools and universities. I would particularly like to thank the Western Sydney University where I received my Law degree and the University of Wollongong where I obtained my Masters degree in Law – an experience which enabled me to realise my dream of becoming a court room advocate. Australia educated me. How lucky I became. How lucky is any person who receives an education in a free land and goes on to use it in daily life.

In 1987, the year before the Australian Bi-Centennial celebrations, I was among many young children forcibly removed from their homes and families and marched to Ethiopia, for reasons that were unknown to me at the time. I walked thousands of kilometres without shoes or underwear.

What do we take for granted as Australians? Free education, food, clothing (more than shoes and underwear), shelter , health care and personal safety. We take those things for granted until we don’t have them.

I witnessed children like myself dying as we made our way, bare]foot and starving. As a child, witnessing the death of a relative is something that stays with you for life. Even today, I remember the deadened face and the gaunt skeletal body of one of my nephews lying on a corn sack. I saw too much abuse and death among my friends during the war. I sustained physical abuse from my superiors because of my inability to follow orders and for demanding decent treatment. I was a child soldier and I was expected to kill or be killed.

Within a year I was plagued by disease and malnutrition. I felt isolated and deserted. I remember being told off by one of my close relatives in 1989 because I was poking him with my protruding bones. He too was a forced conscript. We were stationed in a camp in Western Ethiopia that was disguised as though it was a refugees’ camp. He told me I should just die. I understand now that he too was suffering from depression and by caring for me he was unable to improve his own situation. By this time, I could only take fluids. I feel sorry for my relative. I do not believe that he was trying to be cruel. He was just a child too, unable to properly look after me or himself.

In those days, what I needed was a loving parent. What child, taken away from the care of his or her parents will not suffer some form of psychological trauma? What child, merely seven years of age and ordered to witness deaths by firing squads will not suffer a lasting injury? What child, upon seeing dead bodies, lying in pools of moving blood, will not suffer some sort of long term psychological damage?

Around 1993, I watched some boys, only 10 or 11 years old, as they picked up their AK47s, put the gun to their heads, squeezed the trigger with their own fingers and blew out their brains. In a better world those fingers might have made music in a place such as this hall, built homes, operated the equipment of scientific discovery. Instead their short lives were as nothing – innocents destroyed. I, consumed by fear, couldn’t pull a trigger myself, because I was too scared. Yes, fear saved me. But I understand why they did it. For my fellow child soldiers, pulling the trigger was the quickest way to die and for them the thought of dying was better than the reality of living.

I wonder what their spirits would have thought if they saw that I would become a practising lawyer in Australia some 18 years later. I grieve for them. For them the freedom from fear was death. I was lucky. You are too. Freedom from fear is about acceptance of our common identity. For we Australians in 2016 freedom from fear is almost taken for granted. We had better take care to keep it.

Let me turn now from memories of death to messages of hope, first for new arrivals to these shores and then to those who have long called Australia home.

To those recently arrived, do not give up the dream that brought you here. Within every Australian community there are people who were immigrants or whose parents were immigrants. Treat the experiences that brought you here as tough training for the journey of establishing new lives, new families, new careers.

Clover Moore in that same speech I mentioned earlier noted that, ‘The Australian national anthem has promised that, for those who’ve come across the sea, we’ve boundless plains to share’. Surprise! Surprise! Australia is a nation where most of us, most of the time, seek to give and receive a ‘fair go’ and ‘respect democracy’. It’s that ‘fair go’ that you see in every new Australian success story. That is the ‘Advance Australia Fair’ in the anthem.

I know that some who are watching and listening will be wondering why I, so black, am ignoring that the ruling majority appear to be white. I don’t ignore it, just as I don’t ignore that the colours and faces of the Australian community are such a rich palate. Take a trip around an Australian city, visit a building site, walk around an educational campus, look at the names in our sporting teams, and hear, see, smell, and taste the richness of the cultures in any of our shopping centres. White is a colour to which so much can be added.

I remind every youthful migrant to remember and cherish where you came from. It is your grounding, just as important to you as this land is to the traditional owners of this place. Your parents and relatives made sacrifices for your freedom to be here without fear. You must have a dream that takes you up and beyond any past trauma and turmoil. We are special, each and every one of us. You are special to this nation and you ought to listen to your heart and take hold of opportunities.

Of course fears arrive unbidden and unwelcome. We all experience that from time to time. Can we get and keep a job? How do we keep our cherished cultural traditions alive? Can we earn respect? Will we be listened to? But don’t fight your fears alone. Here we have the freedom to seek help from new friends, the elders, even a stranger who can be your friend at the time you need them. Remember, fellow immigrants, we begin as strangers in this land and we have much to learn. But the freedoms of this place mean that most of the time, from most people, there is a welcoming hand. So fear not.

That leads me to those who are settled Australians. This past few years there have been unexpected fears, the fears that random atrocities such as those that took place in Bali, and more recently in London, Paris and Istanbul will come here. We scarcely notice the frequency of such acts in other places where terror, not freedom from fear, is the norm.

Fears and doubt are the ideal environment in which to breed misguided obsessions and grand delusions. There is nothing new in such manipulation. It was done to me. Such manipulation of the confused and searching spirit of youth is essential for those who use others in their quest for power.

In responding to tragedies in which the lives of victims and perpetrators alike have been snuffed out to serve some demagogue, we must all be careful not to let local opportunists exploit our emotions with simplistic solutions.

What seems new for we Australians is that the physical barriers to terror such as distance and sea are now irrelevant. But this is just the shortness of memory. These barriers became irrelevant for the traditional owners of this land when the winds and the currents brought the ships of the First Fleet up this Harbour. More recently these barriers were no barriers at all when a midget submarine entered Sydney Harbour during the Second World War.

Then as now freedom from fear is something that must be fought for. It can never be taken for granted. Fighting must sometimes be physical and our War Memorials are testament to those who fought and gave their all. But the first line of defence against consuming fear is always our collective hearts and minds.

And collectively what makes this Nation one to be proud of is the willingness of most in our communities to be accepting, tolerant, inclusive and welcoming. Our anthem speaks of the courage needed to let us all combine. Now is the time.

The fears among us are not limited to terrorism. It is all too clear that partner abuse and child abuse flourished in families where the victims were afraid to speak out. It is not so long ago that gays and lesbians lived in fear of exposure. Attitudes and actions needed to change and that has happened, but there is still more to be done.

This afternoon, I delight in thanking all those whose support for ‘freedom from fear’ never wavers. These are the people, the people all around us, who freely gave me hope and sustained it. They understand the journey that has brought new arrivals to these shores from war, famine, oppression, and which then becomes the new journey that follows a new path, a path of ‘freedom from fear’.

The spirit of giving walks that same path to remind us all about the less fortunate. The reward of freedom from fear has a price: to willingly give for others without hope of anything beyond ‘thanks’. This is an obligation that never ends.

One of my early Australian friends illustrates this point. He bought me my first bicycle and got me a job to mow lawns. Geoff died a decade ago, and I shall always remember him for his encouragement, his faith, and his investment in me.

There are now so many friends, colleagues, and teachers who all in different ways have led me here. I thank you all, not only for your help to me but the likely help you have given others too.

Last but not least, my gratitude is to fellow Australians for opening the door, not only to me but to all the other migrants like me. Without your spirit of a fair go, my story could not have been told.

We acquire our community wisdom from our collective, shared experiences.

It’s that wisdom, which underlies our entitlement to sing in joyful strains how proud we are today to be Australians.

Let’s look at the future. My guru told me to live so that I can build a living memorial for my departed loved ones. There will be a charitable foundation in the name of my murdered brother, John Mac. We will raise funds and take action to alleviate poverty, bring education and better health to the lands where I was born and he died.

I will try to follow in the footsteps of a man who wanted to make things right.

I hope that I can be like my friend Geoff, giving less fortunate people a fair go.

I hope that all of us, each in our own way, will strive to understand and help others.

I wish us all a Happy Australia Day.