In my ongoing journey as a community advocate, I’ve had the privilege—and sometimes the challenge—of working closely with both regular community members and leaders. My recent reflections on the complex mechanics of achieving social transformation through collective effort have highlighted some key issues. In my last two posts, I discussed the power of conversation in initiating change and the intricate dynamics of managing those conversations and interactions when working towards a common vision. In this third piece, I want to delve into a particularly challenging aspect: resolving disagreements and disputes within our communities, especially in the context of community associations that are often formed based on nationality, language, or ethnicity.

Often the idea of forming a community structure or entity is circulated in the community many people embrace it and there is excitement and goodwill in being part of the initiative. While many come together with the noble intent of improving their communities, things tend to become quite complicated when discussing power and politics that are ultimately connected for such projects. My experience within African-Australian communities has shown a lot of us struggle to handle the politics and politicking that are connected to filling the roles and responsibilities for the organisation that everyone is calling for and want to see thriving. Often the issues arise because of the prestige—real or imagined—associated with leadership positions versus the ambitions both legitimate and excessive that various individuals might have.

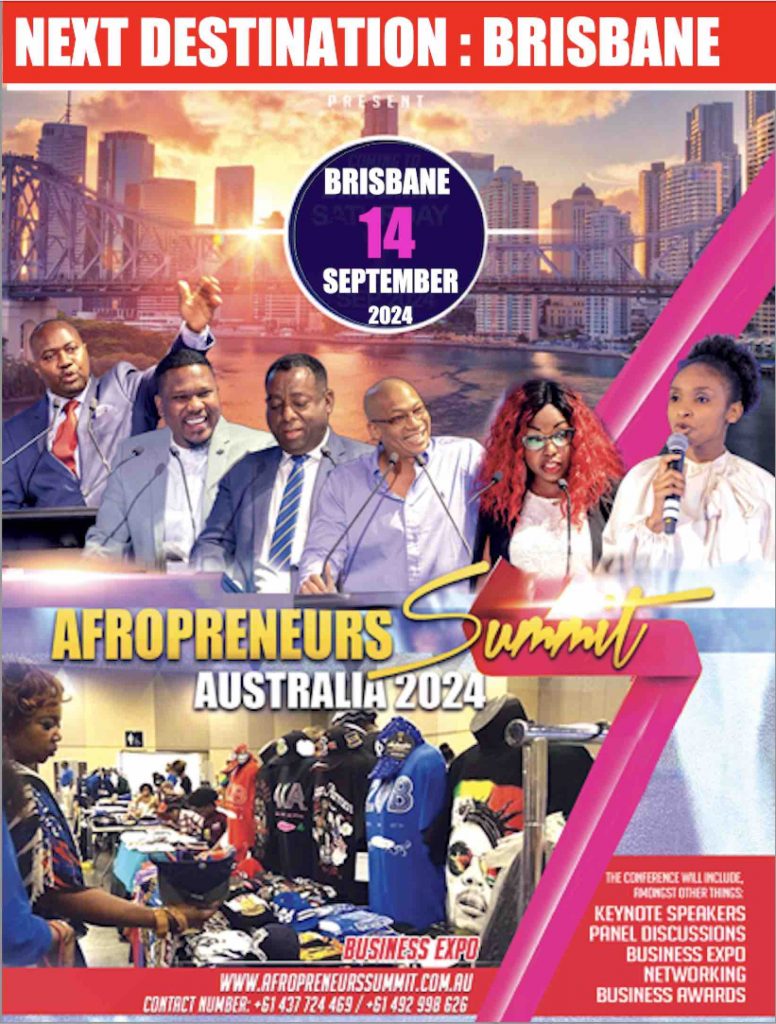

African Community leaders having a discussion in Footscray in Melbourne

In these settings, I’ve observed the emergence of three distinct groups. Firstly, those who believe the best person in the group should lead and be given enough support and space to do what it takes to elevate the community. Such people are able to capture the value that one or two people in the group can bring to the whole group because of their elevated skills, creativity, connection and dynamic leadership style. They let the leader chose his/her team to work with and be accountable to the general assembly.

The second group is made of people who believe in shared leadership style, where the leader is kept in check by an executive or leadership team. Here people believe that leadership of the group must be given to the whole of the executive team rather than to the best leader in the group. The leadership style is therefore collegial, and any leadership initiative or activity must be controlled by the executive team, which is that is made of different people who might nor might not necessarily be close to each other and might not even like each other.

The third group is made of people who are quite informal in their structure and style of leadership. In such groups it is often the person who is able to mobilise the most member of the community who becomes the defacto leader, whether they have sufficient leadership qualities or not. Often in such groups those who, due to personal dislike or jealousy, either openly or covertly undermine the leader, often wishing to see them replace or even take their place

Each of these group experience disagreements, but the way they handle it is different.

As human beings we think differently, we have different ambitions, different ways of handling our emotions and managing our desires. Because of this, disagreements, division and conflicts are inevitable in any group. What differ from one group to another, from one community with another is the way these differences are handled. Those groups that are the best at addressing divisions and conflicts enjoy stable and effective leadership, which often translate into better outcomes for the broader community.

Many of our migrants groups struggle with the politics of community leadership, and regular members are not always willing to be led or to support good leaders through constructive actions. Simple disagreements can escalate into heated debates or even aggressive behavior, turning minor issues into significant problems.

One of the underlying reasons for this is the diverse demographics within these community associations. They often include a mix of professionals with advanced education, individuals with average education, and those with little to no formal education. Additionally, there is a blend of recent arrivals whose mindsets are still shaped by “bush/village thinking” and those who hold onto tribal or ethnic biases that have no place in a modern society like Australia.

Leadership within these groups also plays a critical role. Even well-intentioned leaders sometimes act too quickly or make decisions without consulting their peers or the broader community, often because circumstances demand rapid action or because the leader believes it is the right course, regardless of group consensus. This “captain’s call” approach can lead to further discord, particularly when things go wrong.

When disagreements arise, resolving them without fracturing the group’s cohesiveness is often challenging. Emotional thinking is pervasive, making it difficult to address mistakes constructively. As a result, even though we talk about unity, many of us struggle to practice it effectively. Achieving and sustaining unity in African communities is exceptionally difficult, and this undermines many of our initiatives, preventing them from growing into lasting institutions.

As a consequence, those in our community advocacy organisations who have achieved significant milestones are often individuals who either worked mostly alone, relying on close friends or some external support, or those who managed to assemble a tight-knit leadership team that is both visionary and dynamic.

One of the consequences of the poor handling of disagreements within these community entities is that many highly educated and successful professionals often decide to distance themselves from anything related community. They do this to shield themselves from the attacks, disrespect or humiliation that they have either been victim of or have witnessed other people falling victim to. In doing so they leave the leadership of the community in the hands of those who may lack the necessary skills to achieve significant progress for the group. Many people confuse the ability to mobilise the community on something and the leadership skills in achieving adequate and effective advocacy in the context of the realities of the broader Australian society

The above dynamic creates a cycle where our communities struggle to advance, despite the willingness, potential and vision that bring us together. If we are to overcome these challenges, we must learn to handle disagreements more harmoniously, support our leaders constructively, and focus on building unity that can withstand the inevitable differences that arise when people work together. Only then can we hope to transform our communities into thriving, sustainable institutions.